“Chef Gary, how do you get a position like this?” asked one manager from a regional hardware chain after I packed up the last of our grill equipment into my car. His question surprised me. The manager was referring to my role as a “Weber Grill Ambassador” or “Weber Grill Demonstrator.”

“Well, first you need a Ph.D.,” I quipped.

We all laughed, but the humor helped me avoid answering an awkward question. I really felt availability was the chief asset. With no formal training in cooking, I resist the “chef” title and have asked others not to apply it to me, with little effect. “But I like calling you chef,” said the manager in response, and so now I relent. Really, I still think that title implies that I have credentials that I don’t possess, formal training beyond my careful study of Weber cookbooks, familiarity with cooking various meals on my different Weber grills, and experimenting with different grill cooking methods at home. It’s true: I am a “Weber Grill Ambassador” and “Weber Demonstrator.” Yet, I still hesitate when checking the box beside “Weber-trained” on the demonstration form after each cook. Maybe it’s because I spent so much of my professional life attaining credentials like the PhD that I’m thinking the rest of the world operates under the same rigors. I know that isn’t true, as I’ve encountered many fine “chefs” without culinary degrees. Margie says I deserve the title. Still, I hesitate.

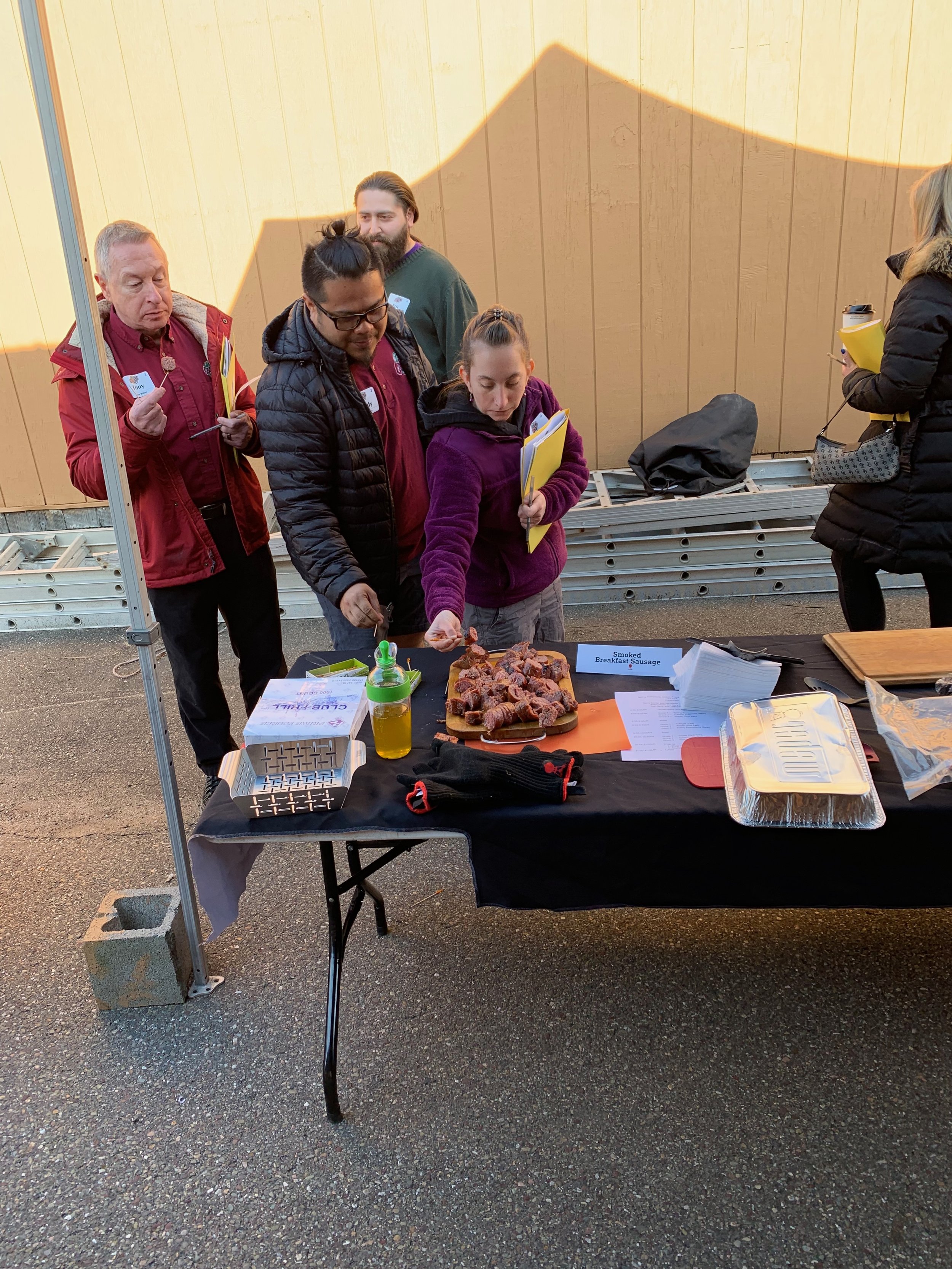

That one Tuesday in late March, I had just served lunch to eighty hungry and grateful employees from various stores in the chain for a spring training event. We stood outside together, shivering in the windy driveway between two large steel fabricated huts—one with open storage and the other with a classroom that also serves as a lunchroom.

Before this event, I had spent a previous summer “demonstrating” Weber grills, meaning I prepared meal samples, chiefly in parking lots at Weber dealers over a weekend. Weber permits me to cook anything I want except “hot dogs and hamburgers” since the purpose of “demos” is to expand the customer’s skills as to what they can cook on a grill. With little guidance, I had to discover what the demonstrator role entailed. I also needed to anticipate the problems I would face when I arrive at a demonstration location. Is the grill ready to fire up? Is there gas in the tank? Has the grill been cleaned? Are there charcoal briquettes or pellets available for hours of cooking? Is there a trash can I can use? Are there two six-foot tables I can borrow for a display with branded tablecloths I brought? Where’s the closest water source for ready cleanup? Finally, will you take a picture of me and the setup, so I can send it to Weber? Whew! My level of comfort depends heavily on whether the dealer has some basic setup when I pull onto the dealer’s lot.

No matter what the hurtles, though, I quickly fell in love with demos. It’s something special about traveling to new locations, talking to customers, and revisiting with Weber enthusiasts. What’s not to like about grilling with the latest equipment on a summer afternoon? With demos, I pick up new skills that spring from the pressure of producing meals on demand.

I had some early opportunities with grilling for a crowd. In early spring, one regional chain of stores train their sales personnel for the spring events that they’ll shortly be hosting. The training consists of three sections, divided between two equal numbers of employees: one group in the morning and another in the afternoon with lunchtime in between. Participants take notes for a multiple-choice test that’s given at each session. One session during each round is allocated for Weber and taught by Ryan Clauss, the Territory Sales Manager for SKKR and Associates, the sales representative agency of Weber-Stephens Products. His knowledge of Weber is deep. Ryan is my immediate boss, but it’s not a title he would apply to himself. He has a management style that is more collegial than directive. He’s always cool under pressure. I spent a week prepping dishes, pre-cooking ones with long cook times, and sealing ingredients in ways that are quick to pop open.

That first Tuesday morning was a cold day when I got up. I arose at 5:30, took a quick shower, and started pulling my overstocked refrigerator filled with marinated meat and veggies sealed in FoodSaver bags. I also had four covered aluminum pans, two filled with macaroni and cheese that I had previously partially cooked in the Weber Smokey Mountain (WSM), along with two ready-to-smoke bean concoctions. I planned to transport this slippery collection using two soft-sided cooler bags.